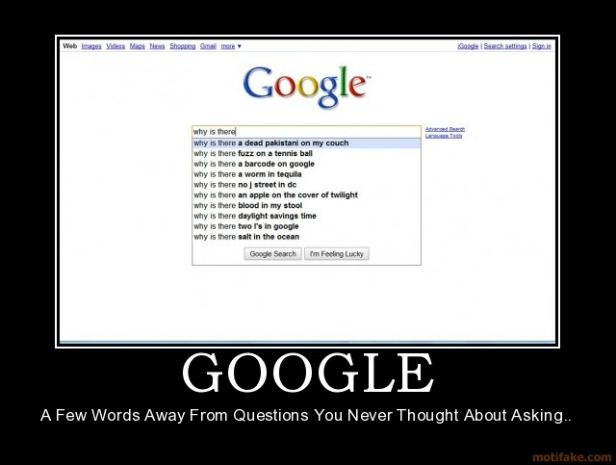

At the heart of this question sits the internet and its vast, seemingly infinite trove of information and more specifically the portal to that information: search engines. Are our brains half-assing it because we know that information is only a few keystrokes and a click or two away? That’s the conclusion from a new study published by Science magazine.

It’s hard for me to even remember a time when I didn’t have to ability to instantly pull up any bit of trivia online. Sure, a couple of years ago it wasn’t that instant – I mean, if I was out I would have to wait until I got home to Google it. But now with the abilities of mobile devices to quickly and efficiently browse the web, any answer to almost any question is only moments away.

Information gathering has become so effortless that I often times deny myself the internet so that I can remember something on my own. Do any of you guys do this? There’s an actor or actress from some obscure film right on the tip of my tongue. I could find it in 15 seconds with my IMDB app, but I don’t. It’s a little game that I play with myself, one that comes with a grand sense of accomplishment when I succeed. It’s the technological version of saying to your friend, “wait, wait, don’t tell me.”

But if I can’t think of what’s on the tip of my tongue in a reasonable amount of time, then of course I head to the internet.

And that tendency is seriously altering the way our brains store information, says Betsy Sparrow. She conducted a series of experiments, mostly on college students, and came to the conclusion that we are using Google as a back-up memory bank.

Basically, we are using the internet in place of another person in a theory proposed decades ago called “transactive memory.” Hashed out, by Science‘s John Bohannon in the analysis of Sparrow’s experiment –

According to the theory, people divide the labor of remembering certain types of shared information. For example, a husband might rely on his wife to remember significant dates, while she relies on him to remember the names of distant friends and family—and this frees both from duplicating the memories in their own brains. Sparrow wondered if the Internet is filling this role for everyone, representing an enormous collective act of transactive memory.

So what she did to test this theory is play a little trick on students. She gave them 40 different trivia statements – banal things like the fact that an ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain. She then had them type the trivia into a computer. She told half the students that the information they typed would be deleted and half that it would save it.

And you guessed it, the half that thought the data was going to be saved did much worse than the half that thought it was going to be erased. The latter group knew they didn’t have a backup, so their brains worked harder to store the memories.

Google is now that backup.

Another part of Sparrow’s experiment is even more interesting than that.

She again gave her subjects random facts to enter into the computers. This time, she told some that each trivia item would be stored in one of six specific folders labeled things like “Facts” or “Items.”

She found that the subjects could remember which folder each fact had been placed at a more impressive rate than the actual fact itself. Even when the students forgot the actual fact, when asked a generic question like “which folder is the ostrich fact in?” the students could point to the right one most of the time.

In short, we are now becoming better at knowing were we can find information than actually retaining that information. We might be teaching ourselves to simply be “good at Googling stuff.”

“I have no idea, but I know how to find out!”

This is some pretty interesting stuff. I wouldn’t say that this proves that Google is making us all dumb, but it might be making our brains lazy.

WebProNews is an iEntry Publication

WebProNews is an iEntry Publication